While I was mindlessly browsing through the various audition videos for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra's YouTube concerto competition last night, I found this. This is an example of what I would call "Absolute Violin Playing." The Bruch Concerto is one piece that I have trouble listening to when played by anything less than an "Absolute" violinist (particularly when it is without accompaniment), but when the opening is played by an "Absolute" violinist, like Odin Rathnam, it becomes an inspiration.

Odin Rathnam plays the Sarabande from the Bach Partita #2

and the last movement of the Mendelssohn Octet

Friday, March 30, 2012

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

The Imaginary Trolls that Live Under the Bridge

I finally understand how to get the richest and most interesting sounds out of my viola and my violin. It all has to do with the mental image of directing the vibrations of the string towards the bridge, using any means necessary. My means are totally related to playing on the outside of the hair and directing the sound towards the bridge, which also gives the feeling that I am directing the sounds towards my heart. When the "trolls" who live under the bridge (I'm imagining cute little ones that are actually more like fairies or imps than trolls, but I like the image of paying a toll to the troll to be able to enjoy the rich sound; it's a mental image, and perhaps it doesn't make rational sense, but this image is sensual, not sensible) get excited, the sound expands and grows rich with vibrations.

Listening to the Julius Baker videos I posted the other day reminds me of the importance of air direction in flute playing. When I play the flute, I use my tongue to direct the airstream to the place that excites the little "trolls" that "live" just below the flute's permanent "reed" on the headjoint.

One danger with flute playing is to compress the air too much (perhaps with the muscles of the face and mouth), and kill the vibrations. The results can range from a sound that is forced and reedy to a sound that is dead and dull, and the rarity of excellent flute playing has to do with the immediate sensibilities of the player and serious control over the whole breathing mechanism and the articulation mechanism. I think it also has to do with the specific flexibility and agility of the tongue, which I understand is mostly genetic.

The various components of the breathing and articulation mechanisms in flute playing are directly analogous to the various components of the bow arm in string playing, but the advantage to string players is that they can breathe freely while they play, and wind players, obviously, cannot. String players can also release tension in their bodies through functional motion, while wind players risk looking conspicuous when they move. In the case of Julius Baker, he managed to deal with every possible aspect of tension mentally (and way ahead of time), so he could remain still, and could let the music do all the work while he was playing.

The big difficulty, with all three instruments is to maintain that overtone richness while moving from note to note. Therein lies both the difficulty and the fascination of the whole process of playing. With string playing there are the variables of string tension, string length, and getting from one string to the next, and with flute playing there are the issues involving the length of the tube, and going from one register to the next.

But once those trolls start to dance, you have to keep them in step and in line, particularly when the music at hand involves double stops!

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Julius Baker Plays the Poulenc Flute Sonata and Villa Lobos Jet Whistle

These performances come from an early 1960s television broadcast. It is interesting to note that the pianist, Vladimir Sokoloff, made recordings with Baker's teacher, William Kincaid.

Advice for Musicians From Their Teachers

I put the following comment on Noa Kageyama's Bulletproof Musician Post (that he presents as a contest). I prefaced my comment with note that my comment is not an actual entry--just a comment.

It's about Julius Baker. I began this blog with a post about Julius Baker, and couldn't resist revisiting my memories of him when I saw Kageyama's question.

I studied flute with Julius Baker for four years (1976-1980) at the Juilliard School of Music. I met Julius Baker when he was in active recovery from a heart attack, and at a time when he was full of a kind of second wind (no pun intended) for living life to the fullest and embracing the idea of good health. He was, at that point, an example for a lot of people. He would get up at five in the morning and jog (he was in his early 60s at the time), and then drive from Brewster to Manhattan (about an hour, if the traffic wasn't bad) for a full day of rehearsing and teaching, and would have a performance at night with the New York Philharmonic. His teaching time was more "social time" than hands-on teaching. Lessons consisted mostly of meeting him for lunch in the faculty part of the cafeteria, and then going as a group to his studio and having masterclass-type lessons. From those classes I learned that it was important for a woman to dress well and look good, it was important to be extremely competent, and that if there were technical problems to be tackled, he was not the person to ask to solve them. He was an extraordinary player who taught by example (he advised his students to jog, for example). He showed us that social skills were of maximum importance, and that you should always be friendly to people, even if you didn't like them much. He always considered himself a "regular guy," and tended to relate to the "regular guy-ness" in people. He would talk to strangers with the intention of brightening their day.

It was very rare to have a private hour-long lesson with Julius Baker. In four years I may have had five or six. One moment in one lesson stands out in particular.

I was working on an etude by Marcel Bitsch. The Bitsch etudes are more like studies in writing for a solo line than they are technical etudes. There were a bunch of notes that made up a lyrical motive, and I suppose I just didn't "get" the sense of how they worked in relation to one another. Julius Baker played the passage for me, and it made a certain kind of sense. Then he likened the passage to playing a jingle (Prior to being the principal flutist for the New York Philharmonic, Baker had been a big freelance recording musician, and made a great living playing radio jingles), and told me that even if the jingle you are playing is not particularly interesting, it is your job to make those notes, those few seconds of music, as beautiful and as interesting as possible.

From that statement I understood that it was applicable to all music. That the job of a performing musician is to make every note and every phrase beautiful and interesting, regardless of the quality of the passage or even the piece. Now that I am older (much older), and know a great deal more about music than I did when I was a Juilliard student, I can apply Julius Baker's lesson in expanded ways. When the music is great--when a passage in question is a gem, your playing has to meet the expectations of the passage so that it can be as beautiful as it should be.

After I made the permanent switch from flute to viola (and violin), my family and I went to Brewster, New York to visit the Bakers, and Michael took this picture.

[Julius Baker, his wife Ruth, and the 39-year-old me on July 18, 1998]

It's about Julius Baker. I began this blog with a post about Julius Baker, and couldn't resist revisiting my memories of him when I saw Kageyama's question.

I studied flute with Julius Baker for four years (1976-1980) at the Juilliard School of Music. I met Julius Baker when he was in active recovery from a heart attack, and at a time when he was full of a kind of second wind (no pun intended) for living life to the fullest and embracing the idea of good health. He was, at that point, an example for a lot of people. He would get up at five in the morning and jog (he was in his early 60s at the time), and then drive from Brewster to Manhattan (about an hour, if the traffic wasn't bad) for a full day of rehearsing and teaching, and would have a performance at night with the New York Philharmonic. His teaching time was more "social time" than hands-on teaching. Lessons consisted mostly of meeting him for lunch in the faculty part of the cafeteria, and then going as a group to his studio and having masterclass-type lessons. From those classes I learned that it was important for a woman to dress well and look good, it was important to be extremely competent, and that if there were technical problems to be tackled, he was not the person to ask to solve them. He was an extraordinary player who taught by example (he advised his students to jog, for example). He showed us that social skills were of maximum importance, and that you should always be friendly to people, even if you didn't like them much. He always considered himself a "regular guy," and tended to relate to the "regular guy-ness" in people. He would talk to strangers with the intention of brightening their day.

It was very rare to have a private hour-long lesson with Julius Baker. In four years I may have had five or six. One moment in one lesson stands out in particular.

I was working on an etude by Marcel Bitsch. The Bitsch etudes are more like studies in writing for a solo line than they are technical etudes. There were a bunch of notes that made up a lyrical motive, and I suppose I just didn't "get" the sense of how they worked in relation to one another. Julius Baker played the passage for me, and it made a certain kind of sense. Then he likened the passage to playing a jingle (Prior to being the principal flutist for the New York Philharmonic, Baker had been a big freelance recording musician, and made a great living playing radio jingles), and told me that even if the jingle you are playing is not particularly interesting, it is your job to make those notes, those few seconds of music, as beautiful and as interesting as possible.

From that statement I understood that it was applicable to all music. That the job of a performing musician is to make every note and every phrase beautiful and interesting, regardless of the quality of the passage or even the piece. Now that I am older (much older), and know a great deal more about music than I did when I was a Juilliard student, I can apply Julius Baker's lesson in expanded ways. When the music is great--when a passage in question is a gem, your playing has to meet the expectations of the passage so that it can be as beautiful as it should be.

After I made the permanent switch from flute to viola (and violin), my family and I went to Brewster, New York to visit the Bakers, and Michael took this picture.

[Julius Baker, his wife Ruth, and the 39-year-old me on July 18, 1998]

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Music Really Happens One Beat at a Time

With all the musical events happening all over the world, all the music that is being written, premiered, and discussed, and all the "talk" about the "industry" of classical music and its various "stars," it is easy to forget that most of the music making in the world happens off the internet grid. It happens between a musician and the pitches he or she is playing. It happens in the isolated spaces of composers who spend ridiculous amounts of time worrying about how best to get from one harmony to the next, or from one note to the next. It happens when performing musicians have rehearsals. It happens in lessons. It happens when people practice, and it happens when people play concerts in places far away from you or from me, and in places that are close by.

Sometimes I get overwhelmed by the amount of musical material I can access instantly using the electronic device I am using to write this blog post. Sometimes I compare the value of access to those riches with the value of being able to find tone colors on my instrument, and (finally) being able to make them at will. When I compare the value of limitless access to recorded music with being able to move comfortably from one note to the next on my instrument, while sounding resonant and in tune, I find much more value in the ability to make something beautiful happen between one note and the next note.

I like to remember that what I am doing when I am writing, practicing, or playing is the same activity or sets of activities that musicians have been doing for centuries. That part of musical life hasn't changed, and I don't think that unlimited access to recorded music and commentary will ever change it. It is a comforting thought.

Sometimes I get overwhelmed by the amount of musical material I can access instantly using the electronic device I am using to write this blog post. Sometimes I compare the value of access to those riches with the value of being able to find tone colors on my instrument, and (finally) being able to make them at will. When I compare the value of limitless access to recorded music with being able to move comfortably from one note to the next on my instrument, while sounding resonant and in tune, I find much more value in the ability to make something beautiful happen between one note and the next note.

I like to remember that what I am doing when I am writing, practicing, or playing is the same activity or sets of activities that musicians have been doing for centuries. That part of musical life hasn't changed, and I don't think that unlimited access to recorded music and commentary will ever change it. It is a comforting thought.

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

March is Busting Out All Over

Yesterday I spent my walk intoxicated by the sounds, sights, and smells of this odd early spring we are having. My usual "Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most" feelings came out stronger than usual this year. So I took action and finished work on the piece I have been working on for the past couple of months, and now it is out of my system and no longer constantly running through my head.

The windows are open, the birds are singing and singing and singing, and I'm planning to join them with some scales in a moment, and then some nice Bach, in honor of his birthday today.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Eliminativism

Matthew Guerrieri coins a new trend in new music!

It is interesting reading next to a post-mortem on the fate of the (formerly named) "women composer" by Amy Beth Kirsten (in the same internet publication).

It is interesting reading next to a post-mortem on the fate of the (formerly named) "women composer" by Amy Beth Kirsten (in the same internet publication).

Monday, March 19, 2012

Our Fourth (and still counting) Annual March Concert of Music Written by Women

John David Moore and I will be playing yet another program of music written by women (sponsored by the Eastern Illinois University Women's Studies Program) in celebration of Women's History Awareness Month. This year violinist Sharilyn Spicknall will be joining us for a program of music by Amy Beach (her Violin Sonata), Marion Bauer (her Viola Sonata), Rebecca Clarke (her Dumka for Violin, Viola, and Piano), Luise Adolpha Le Beau (her Three Pieces for Viola and Piano), and Me (my Skye Boat Fantasie).

The concert will take place on Friday evening, March 23 at 7:30 in the Recital Hall of the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Illinois. Admission is free, and parking is ample.

What's in a name? Marion Bauer was an American composer who, despite her German-sounding name, came from French stock, and Le Beau, despite her French-sounding name, was German.

My name, you ask? Who knows!!!

During the first decade of the 20th century, my paternal great grandfather and his family left a shtetl outside of Kiev, and they sailed for America from a German port. The story I was told was that the ship sank (it must have happened near the port, because eventually my family did arrive in America) and everybody's papers were destroyed.

My (totally unfounded and unproven) theory is that when my Yiddish-speaking ancestors arrived in America without papers they may have been asked the question "who are you?" Perhaps the answer my great grandfather gave was an answer to the question he might have thought he heard, "how are you?" His answer (in English, of course)? "Fine." It is just a hunch, but it does account for the English spelling of the word, particularly when you take into account that the passenger had arrived by way of a German port.

The concert will take place on Friday evening, March 23 at 7:30 in the Recital Hall of the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Illinois. Admission is free, and parking is ample.

What's in a name? Marion Bauer was an American composer who, despite her German-sounding name, came from French stock, and Le Beau, despite her French-sounding name, was German.

My name, you ask? Who knows!!!

During the first decade of the 20th century, my paternal great grandfather and his family left a shtetl outside of Kiev, and they sailed for America from a German port. The story I was told was that the ship sank (it must have happened near the port, because eventually my family did arrive in America) and everybody's papers were destroyed.

My (totally unfounded and unproven) theory is that when my Yiddish-speaking ancestors arrived in America without papers they may have been asked the question "who are you?" Perhaps the answer my great grandfather gave was an answer to the question he might have thought he heard, "how are you?" His answer (in English, of course)? "Fine." It is just a hunch, but it does account for the English spelling of the word, particularly when you take into account that the passenger had arrived by way of a German port.

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Primas Stefan and his Royal Tziganes

I have written a great deal on this blog about Steven Staryk, but I haven't written much about his musical alter ego, Primus Stefan, a Gypsy fiddler par excellence, who was one of the first (if not the first) "legit" violinists to bring traditional violin music from Eastern Europe to more Western ears by way of recordings. In order to become Primas Stefan, Staryk, who had learned to play traditional Eastern European music as a child in Toronto, had to seek out traditional musicians in post World War II Europe, which was no easy task.

Centaur has added two tracks to the second volume of its forthcoming multi-volume retrospective (this disc is CRC 3203, and it should be available soon). One piece is called "Gloomy Sunday," recorded by Primas Stefan in 1959, and the other is the middle section of Sarasate's Ziegeunerweisen.

This Ziegeunerweisen comes from two recordings: the outer parts come from a 1967 recording of the very familiar Sarasate piece (played exquisitely by Staryk and Douglas Gamley conducting the London Festival Orchestra), and the inner part, recorded in 1959 by Primus Stefan and his Royal Tziganes for the recording pictured above, is a traditional setting of one of the popular Gypsy melodies that Sarasate used in his piece.

Staryk served the concertmaster of both London's Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Amsterdam's Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, so the "royal" nature of the Tziganes' name seems quite natural. Copies of the LP are still available, but this "mash up" on the Centaur CD is unique. The disc (Volume 2 of a 2-CD set) is also loaded with Kreisler and other treats. Volume 1 has concertos by Paganini, Beethoven, Mozart, Saint-Saens and Shostakovich.

Check Centaur's website from time to time and do a search for Staryk. These recordings will certainly be listed there soon. If you haven't heard the Beethoven or the "Every Violinist's Guide" that are there, I can recommend them both heartily.

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Dancing about Architecture, Again

The phrase "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture — it's a really stupid thing to want to do" is a catchy phrase, but it has always bothered me, particularly the "really stupid thing to want to do" part, which seems to be Elvis Costello's contribution.

The first part of the phrase that refuses to die has been around since (at least) the 1970s, and many of the people who tend to use it do not seem to be people who spend their time studying and playing the stuff that we call "classical" music.

Writing intelligently about math, science, history, literature, poetry, art, philosophy, or even architecture requires discipline-specific vocabulary. Writing about music does too. The vocabulary is not that difficult to learn, but it takes time to amass, and requires a lot of listening and a lot of observation. Writing intelligently takes work, and it usually reflects intelligent thinking. I don't think that the casual user of the phrase would consider the desire to write about the above disciplines stupid, so why should it be stupid for people to want to write about music, particularly musicians?

I am a consumer of things mathematical, scientific, historical, literary, poetic, artistic, philosophical, and architectural, but I am a producer of music. I'm proud of the music-specific vocabulary I have amassed through years of experience. I feel challenged to unravel a musical mystery and excited when I am able to articulate exactly why a particular musical passage might be strong or weak. I feel proud when I can figure out (as a performer) how to bring out compositional strengths or compensate for compositional weakness in a particular piece of music. I also find it very valuable to be able to articulate interpretive concepts to students.

The first part of the phrase that refuses to die has been around since (at least) the 1970s, and many of the people who tend to use it do not seem to be people who spend their time studying and playing the stuff that we call "classical" music.

Writing intelligently about math, science, history, literature, poetry, art, philosophy, or even architecture requires discipline-specific vocabulary. Writing about music does too. The vocabulary is not that difficult to learn, but it takes time to amass, and requires a lot of listening and a lot of observation. Writing intelligently takes work, and it usually reflects intelligent thinking. I don't think that the casual user of the phrase would consider the desire to write about the above disciplines stupid, so why should it be stupid for people to want to write about music, particularly musicians?

I am a consumer of things mathematical, scientific, historical, literary, poetic, artistic, philosophical, and architectural, but I am a producer of music. I'm proud of the music-specific vocabulary I have amassed through years of experience. I feel challenged to unravel a musical mystery and excited when I am able to articulate exactly why a particular musical passage might be strong or weak. I feel proud when I can figure out (as a performer) how to bring out compositional strengths or compensate for compositional weakness in a particular piece of music. I also find it very valuable to be able to articulate interpretive concepts to students.

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Arts in Competition with One Another

I was rather taken aback to find an announcement about a competition for bloggery about the arts in my mailbox last night. I avoid competitions as a rule, and tend to particularly avoid competitions that are looking for "the best" of anything. I participate in this ever-changing entity that I like to call the musical blogosphere purely for the fun of it, so I'm not throwing my hat into the ring. Besides, I have finals to give during the week that the concert series these people are promoting is being held. And with all the arts at play, I can't imagine how any person or group of people could come up with a single winner.

I am intrigued by the first question, however, so I'll play along.

"New York has long been considered the cultural capital of America. Is it still? If not, where?"

The only thing that is more absurd than trying to decide which of the "arts" is the "best" is to try to decide a location that is superior to another location. I lived in New York for four years, and I had a wonderful time doing so on my limited budget (I was a Juilliard student). When I lived in New York (1976-1980) the city was not as safe as it is today, and it was also not as expensive to live in as it is today. Musicians and artists could find living spaces they could afford. There were day jobs that people could get, because making the city work required people punching typewriters and sending messages from one place to another. Jobs for musicians were not plentiful, but there was still a chance, if you knew the right people, and always played the right notes and the right rhythms, that you could get an array of musical jobs in the city that paid the rent.

I recall that admission to most museums used to be either free or nominal, and it was always possible for me to sneak into concerts during intermission, go to cheap double features at the Thalia, and find bargains at the thrift stores on Third Avenue. I imagine that security is tighter at concerts these days, and I know that movies are very expensive in Manhattan, and things you used to buy at thrift stores have now become vintage items, collectibles, and antiques. It's only been 30 odd years since I lived there. Things change.

I miss telephone booths, the book and record stores, and coffee shops that served only two kinds of coffee: regular and black.

But I digress.

After I graduated from Juilliard I went to Europe, where I was extremely excited to experience culture on an entirely new level, historical and otherwise. In Vienna I found that the museums (which were also free at the time) had mind-boggling collections. I found the culture extremely stimulating (and the coffee was too). I had an American friend who introduced me to the Jazz world of Vienna, a world I knew I never would have gained entry to in New York, and I was welcomed into various other social artistic circles that I never would have been welcomed into in New York.

I only spent a small amount of time in Germany, but I enjoyed the museums I visited immensely. Italy was a total feast, both visually and gastronomically. Never once did I long for New York for its museum culture, its musical hierarchies, the speed at which people tended to play, and the way people had to hustle to get ahead in the musical world.

I love visiting New York, and I always feel at home there. Like any city it has its high points (always personal) and low points (also always personal). My last visit to the Guggenheim museum was a total disappointment, and the Whitney always seems to be hit and miss. I tend to find the "ahead of the trend" visual art scene in New York (reflected in the exhibits at those two museums) on the pretentious side. Sometimes I'm pleasantly surprised.

I'm glad that I live in a place where I can enjoy art and music in many cities. From my perch in Illinois I can visit Chicago, Indianapolis, St. Louis, and the smaller cities (that also have art and music) like Champaign-Urbana and Terre Haute (surprising, I know, but I love the Swope Museum). I love my family in Los Angeles (where there is a huge supply of art to see and music to hear) and Boston, and I love my friends in New York, but I just don't consider it an artistically superior place to the other cities I have lived in or visited.

I am intrigued by the first question, however, so I'll play along.

"New York has long been considered the cultural capital of America. Is it still? If not, where?"

The only thing that is more absurd than trying to decide which of the "arts" is the "best" is to try to decide a location that is superior to another location. I lived in New York for four years, and I had a wonderful time doing so on my limited budget (I was a Juilliard student). When I lived in New York (1976-1980) the city was not as safe as it is today, and it was also not as expensive to live in as it is today. Musicians and artists could find living spaces they could afford. There were day jobs that people could get, because making the city work required people punching typewriters and sending messages from one place to another. Jobs for musicians were not plentiful, but there was still a chance, if you knew the right people, and always played the right notes and the right rhythms, that you could get an array of musical jobs in the city that paid the rent.

I recall that admission to most museums used to be either free or nominal, and it was always possible for me to sneak into concerts during intermission, go to cheap double features at the Thalia, and find bargains at the thrift stores on Third Avenue. I imagine that security is tighter at concerts these days, and I know that movies are very expensive in Manhattan, and things you used to buy at thrift stores have now become vintage items, collectibles, and antiques. It's only been 30 odd years since I lived there. Things change.

I miss telephone booths, the book and record stores, and coffee shops that served only two kinds of coffee: regular and black.

But I digress.

After I graduated from Juilliard I went to Europe, where I was extremely excited to experience culture on an entirely new level, historical and otherwise. In Vienna I found that the museums (which were also free at the time) had mind-boggling collections. I found the culture extremely stimulating (and the coffee was too). I had an American friend who introduced me to the Jazz world of Vienna, a world I knew I never would have gained entry to in New York, and I was welcomed into various other social artistic circles that I never would have been welcomed into in New York.

I only spent a small amount of time in Germany, but I enjoyed the museums I visited immensely. Italy was a total feast, both visually and gastronomically. Never once did I long for New York for its museum culture, its musical hierarchies, the speed at which people tended to play, and the way people had to hustle to get ahead in the musical world.

I love visiting New York, and I always feel at home there. Like any city it has its high points (always personal) and low points (also always personal). My last visit to the Guggenheim museum was a total disappointment, and the Whitney always seems to be hit and miss. I tend to find the "ahead of the trend" visual art scene in New York (reflected in the exhibits at those two museums) on the pretentious side. Sometimes I'm pleasantly surprised.

I'm glad that I live in a place where I can enjoy art and music in many cities. From my perch in Illinois I can visit Chicago, Indianapolis, St. Louis, and the smaller cities (that also have art and music) like Champaign-Urbana and Terre Haute (surprising, I know, but I love the Swope Museum). I love my family in Los Angeles (where there is a huge supply of art to see and music to hear) and Boston, and I love my friends in New York, but I just don't consider it an artistically superior place to the other cities I have lived in or visited.

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

A Wonderful Time to be a Musician

DICK GORDON: [it] must have been such a wonderful time to be a talented musician in New York.What a treat it was to hear this interview with the 97-year-old pianist Frank Glazer.

FRANK GLAZER: . . . It’s a wonderful time to be a musician any time.

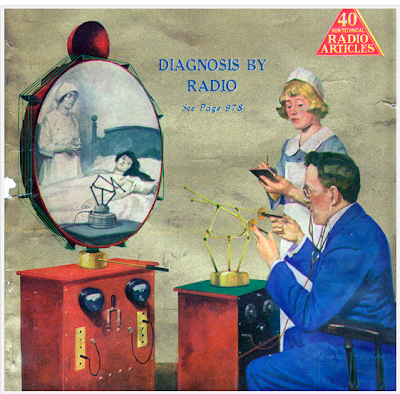

Telemedicine Post at Paleofuture

This picture comes from the cover of a 1925 issue of Science and Invention magazine, and I found it at Paleofuture.

While you are at the Smithsonian site, make sure to check out this (far too short) video about getting sound out of old recordings.

Monday, March 12, 2012

The Difference is in the Doing

I think that one difference between what we call "classical music" and what we might call "popular music" or "commercial music" (including music written in the various idioms used for what we call "classical music") has a lot to do with the motivations of a composer. The same composer can, of course, write music that is intended to be commercial as well as write music that is done with little regard for how it sells (or is consumed). There have always been great composers who wrote both commercial (or popular) and non commercial music. I suppose it has a lot to do with who the consumer of the music happens to be, and how s/he consumes it.

I believe that commercial music is written primarily to engage audiences. Film music is written to manipulate an audience to react to visual images and narrative in a particular way. Opera is too, and even more so in the 20th century. What we call "pop music" is very intensely geared to appeal to an audience, and it is "consumed" mostly by people who are not practicing musicians. Vocal pop music is often defined by a singer (or THE singer) connected with a song rather than the composer of a song, unless it happens to be a rare instance when it is the same person. In the case of the singer-songwriter, the idea of writing the song in the first place seems to be about sharing an emotional experience directly with an audience, where it is often consumed like "pop music," but is then "covered" by people who want to sing it themselves (and often not for an audience).

I assume that I'm not alone when I mention that communicating something to an audience is the last thing I have in mind when I write a piece of music. I write music in order to communicate with musicians and allow communication between the musicians who are playing the music I write. It is their business to communicate their interpretation to an audience. My job ends (if all goes well) where their jobs begin.

I have read that Telemann's motivation for writing music was to give people music that they enjoyed playing. I believe that Bach's motivation was similar, but he also had a job where his music needed to demonstrate the teachings of the Lutheran church. He managed to combine the whole enjoyment of playing thing and the manipulation of spirit thing rather seamlessly. Even people who describe themselves as not the least bit religious are moved emotionally when they listen to Bach's religious music. Instrumentalists who play Bach's non-religious music find personal enjoyment in the process of practicing it. And the personal enjoyment is something that we experience daily. For most of us there is no need to perform Bach's music. We play it because of what it does for us in our own private spaces.

Haydn and his contemporaries published string quartets so that people could play them for collective enjoyment. The challenges and jokes that he put in his music are there to enhance the private musical discourse. When Mozart wrote his "Haydn" Quartets, he did so as a way of communicating with a composer he admired. I believe that the idea of performing them for an audience would have been the furthest thing from his mind. The commercial success for most of the composers of the Classical Period came from the sales of their music. It's kind of like the concept of commercial success for Milton and Bradley comes from the sales of their games.

Sure, Mozart and Haydn did write music that was intended for audiences, and those audiences were often important ones that included monarchs and patrons, but I believe that some of their "public" music was different from the music that they wrote for their friends and for musicians they admired. I think that they wrote chamber music and piano music primarily for people to enjoy playing, and I believe that they always wrote their orchestral music (particularly Haydn, who had standing relationships with the members of his orchestra) so that the musicians would enjoy themselves while playing it. In Beethoven's later years he cared a great deal about what audiences thought of his Quartets (like the late Quartets), but those people were often musicians themselves, and Beethoven was an exception to all rules.

Moving forward to the period of uncommon practice (a.k.a. today), composers write their music for musicians to play and enjoy. The idea of the standard musical ensemble has expanded greatly. There are a great number of percussionists who like to use large numbers of instruments. There are people who enjoy using sophisticated electronic instruments, people who have expertise using extended techniques, microtones, and multiphonics, and people who enjoy exploring non western scales. Many of these musicians are young, and many are interested in playing new music written by people of their generation. The existing repertoire would be very small (if existent at all) for an ensemble made of tuba, percussion, flute, harp, bassoon, and French horn, and for such an ensemble to survive as a performing group, it would need good new music to play. I like to think that composers who would write for a young ensemble like the hypothetical one above would be more concerned about how playable the harp part is, if the bassoon can be heard above the tuba, or whether the percussionist can participate in the ensemble without dominating, than how an audience will respond to his or her musical ideas.

Members of the listening public and consumers of recorded music should remember that there is a lot of new music that is not being written for your enjoyment. It is being written for the enjoyment of the intended performing musicians, and for the enjoyment of other ensembles made of the same instruments as the intended ensemble. If they succeed at communicating the essence of a piece of new music to you, they have succeeded in their mission. If they don't, it could have something to do with the composer (who, if given a chance to hear a performance, can correct the problems in the work), or it could have something to do with errors of judgement (or notes, or rhythms) made by the performing musicians.

I really don't believe that contemporary composers should be judged against composers from a previous eras. I don't believe that living composers should be judged against dead ones. (The living composer can grow, and the dead one can't.) I also don't believe it is fair to judge a composer from the "common practice" period against a composer from what I call the "uncommon practice" of the present day. There will never be another Rameau, J.S. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Schumann, Debussy, Bartok, Ravel, Stravinsky, or Shostakovich (to give just a few examples). These were all singular musical personalities who continue, long after their lives ended, to challenge our imaginations and remain relevant and modern. I believe they all speak to the musicians who play their music now with the same voices they spoke with while they were living, but as "consumers" of music (everyone reading this post is probably, on some level, a consumer of music) we need to keep an open mind about what the music of today means to today's young musicians. The best stuff will survive because people will want to play it, and the stuff that nobody wants to play might have to wait for another generation to find musicians who appreciate. It could also simply fade into oblivion. Only time will tell. While we wait, musicians will still enjoy playing music written by the composers on the above list and by composers who may have not been as well respected or well known during their lifetimes.

I'll end this little rant by paraphrasing a statement I heard Stephane Wrembel make about the influence Django Reinhardt has on him: you can work under the shadows of great composers, or you can be illuminated by their light.

I believe that commercial music is written primarily to engage audiences. Film music is written to manipulate an audience to react to visual images and narrative in a particular way. Opera is too, and even more so in the 20th century. What we call "pop music" is very intensely geared to appeal to an audience, and it is "consumed" mostly by people who are not practicing musicians. Vocal pop music is often defined by a singer (or THE singer) connected with a song rather than the composer of a song, unless it happens to be a rare instance when it is the same person. In the case of the singer-songwriter, the idea of writing the song in the first place seems to be about sharing an emotional experience directly with an audience, where it is often consumed like "pop music," but is then "covered" by people who want to sing it themselves (and often not for an audience).

I assume that I'm not alone when I mention that communicating something to an audience is the last thing I have in mind when I write a piece of music. I write music in order to communicate with musicians and allow communication between the musicians who are playing the music I write. It is their business to communicate their interpretation to an audience. My job ends (if all goes well) where their jobs begin.

I have read that Telemann's motivation for writing music was to give people music that they enjoyed playing. I believe that Bach's motivation was similar, but he also had a job where his music needed to demonstrate the teachings of the Lutheran church. He managed to combine the whole enjoyment of playing thing and the manipulation of spirit thing rather seamlessly. Even people who describe themselves as not the least bit religious are moved emotionally when they listen to Bach's religious music. Instrumentalists who play Bach's non-religious music find personal enjoyment in the process of practicing it. And the personal enjoyment is something that we experience daily. For most of us there is no need to perform Bach's music. We play it because of what it does for us in our own private spaces.

Haydn and his contemporaries published string quartets so that people could play them for collective enjoyment. The challenges and jokes that he put in his music are there to enhance the private musical discourse. When Mozart wrote his "Haydn" Quartets, he did so as a way of communicating with a composer he admired. I believe that the idea of performing them for an audience would have been the furthest thing from his mind. The commercial success for most of the composers of the Classical Period came from the sales of their music. It's kind of like the concept of commercial success for Milton and Bradley comes from the sales of their games.

Sure, Mozart and Haydn did write music that was intended for audiences, and those audiences were often important ones that included monarchs and patrons, but I believe that some of their "public" music was different from the music that they wrote for their friends and for musicians they admired. I think that they wrote chamber music and piano music primarily for people to enjoy playing, and I believe that they always wrote their orchestral music (particularly Haydn, who had standing relationships with the members of his orchestra) so that the musicians would enjoy themselves while playing it. In Beethoven's later years he cared a great deal about what audiences thought of his Quartets (like the late Quartets), but those people were often musicians themselves, and Beethoven was an exception to all rules.

Moving forward to the period of uncommon practice (a.k.a. today), composers write their music for musicians to play and enjoy. The idea of the standard musical ensemble has expanded greatly. There are a great number of percussionists who like to use large numbers of instruments. There are people who enjoy using sophisticated electronic instruments, people who have expertise using extended techniques, microtones, and multiphonics, and people who enjoy exploring non western scales. Many of these musicians are young, and many are interested in playing new music written by people of their generation. The existing repertoire would be very small (if existent at all) for an ensemble made of tuba, percussion, flute, harp, bassoon, and French horn, and for such an ensemble to survive as a performing group, it would need good new music to play. I like to think that composers who would write for a young ensemble like the hypothetical one above would be more concerned about how playable the harp part is, if the bassoon can be heard above the tuba, or whether the percussionist can participate in the ensemble without dominating, than how an audience will respond to his or her musical ideas.

Members of the listening public and consumers of recorded music should remember that there is a lot of new music that is not being written for your enjoyment. It is being written for the enjoyment of the intended performing musicians, and for the enjoyment of other ensembles made of the same instruments as the intended ensemble. If they succeed at communicating the essence of a piece of new music to you, they have succeeded in their mission. If they don't, it could have something to do with the composer (who, if given a chance to hear a performance, can correct the problems in the work), or it could have something to do with errors of judgement (or notes, or rhythms) made by the performing musicians.

I really don't believe that contemporary composers should be judged against composers from a previous eras. I don't believe that living composers should be judged against dead ones. (The living composer can grow, and the dead one can't.) I also don't believe it is fair to judge a composer from the "common practice" period against a composer from what I call the "uncommon practice" of the present day. There will never be another Rameau, J.S. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Schumann, Debussy, Bartok, Ravel, Stravinsky, or Shostakovich (to give just a few examples). These were all singular musical personalities who continue, long after their lives ended, to challenge our imaginations and remain relevant and modern. I believe they all speak to the musicians who play their music now with the same voices they spoke with while they were living, but as "consumers" of music (everyone reading this post is probably, on some level, a consumer of music) we need to keep an open mind about what the music of today means to today's young musicians. The best stuff will survive because people will want to play it, and the stuff that nobody wants to play might have to wait for another generation to find musicians who appreciate. It could also simply fade into oblivion. Only time will tell. While we wait, musicians will still enjoy playing music written by the composers on the above list and by composers who may have not been as well respected or well known during their lifetimes.

I'll end this little rant by paraphrasing a statement I heard Stephane Wrembel make about the influence Django Reinhardt has on him: you can work under the shadows of great composers, or you can be illuminated by their light.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Midnight in Venice

It is interesting to compare these two pieces:

Antonio Lauro's Vals Venezolano #2

Stephane Wrembel's Bistro Fada

Antonio Lauro's Vals Venezolano #2

Stephane Wrembel's Bistro Fada

Musical Chairs

You can learn a great deal about the professional musical world by exploring this appropriately-named website. Make sure to notice how many youth orchestras there are in the United States, and those are just the ones who know about this site (where you can post information about the active organizations in your neck of the musical woods). I found the jobs category particularly interesting.

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Hans Bach

I love this woodcut portrait (made in 1617) honoring the first professional musician we know of in Johann Sebastian Bach's family tree. Hans Bach lived from around during the middle third of the 16th century and died in the second decade of the 17th century (the date here reads 1615). He worked as the fool at court of Ursula, Duchess of Wurtemberg.

Notice the nifty little fiddle in one hand, and the glass of beer or wine in the other. And I love the way Hans is surrounded by pictures of his carpentry tools. Johann Sebastian could have looked at this picture of his great grandfather with some of the same amusement and wonder that we have. Check out the odd hanging thing with a bell on the end next to the word "Laborios." I suppose it would be one of the tools of his jester trade, just like the other stuff might represent the tools of his other job at court.

The Latin caption calls him a celebrated witty fool, a laughable player (I suppose "fidicen" could be a pun on fiddle), and a hard working man who is unaffected and pius.

Notice the nifty little fiddle in one hand, and the glass of beer or wine in the other. And I love the way Hans is surrounded by pictures of his carpentry tools. Johann Sebastian could have looked at this picture of his great grandfather with some of the same amusement and wonder that we have. Check out the odd hanging thing with a bell on the end next to the word "Laborios." I suppose it would be one of the tools of his jester trade, just like the other stuff might represent the tools of his other job at court.

The Latin caption calls him a celebrated witty fool, a laughable player (I suppose "fidicen" could be a pun on fiddle), and a hard working man who is unaffected and pius.

Friday, March 09, 2012

Thursday, March 08, 2012

Lack of Mentors? Thoughts about Thoughts about International Women's Day

I was pleased to see an acknowledgement of International Women's Day in the musical blogosphere. In his take on why "there are so few female composers" Tim Rutherford-Johnson provides a list of mostly living 20th and 21st-century composers who have written avant-garde music (that has been recorded). His idea that the lack of teachers and mentors is responsible for the dearth of female composers (there isn't a dearth, by the way) misses the mark.

Nadia Boulanger was, by all accounts, the most important composition teacher of the 20th century. She was also an excellent composer, but she stopped writing after the death of her sister Lili, who was, even as a very young person, one of the finest composers of the 20th century, of either gender. One of the reasons I think Nadia Boulanger devoted herself to teaching rather than to composition was that she felt that, perhaps, she could help develop other composers develop the way she helped Lili develop. Many of her students were women (you can find an incomplete list of her students here.) In addition to her composition students there are a large number of analysis students on the list. A great part of teaching composition is teaching analysis.

From where I sit in the 21st century I can clearly see an early-20th-century trend involving the rise of women as artistic and literary figures as well as important figures in the sciences. (Madame Curie and Rosalind Franklin are two examples that come to mind). And then somewhere in the middle of the century, perhaps around the time of McCarthyism and the prominence of Virgil Thomson as a music critic (click here for google search for the term Virgil Thomson and Misogyny, though most of the material that comes up is from Google Books) women were forced back to the margins of creative culture.

Marion Bauer is an example of a first rate composer who fell victim to Thomson's mysogyny. He deemed her too conservative to be considered an equal to the 20th century composers he admired. I imagine that he found her to be intimidating (she was a far better composer than he was), and that he used his power of influence to try to take her down.

A couple of female-friendly decades followed Thomson's death (friendly to women who were composers and women who did other creative things), and though we don't yet have an Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, at least as of 2009 women are legally entitled to get equal pay for equal work.

I fear the the neo (or pseudo) McCarthyites that have invaded the second decade of the 21st century are trying their darnedest to marginalize women once again. With the marginalization of women as composers, even retrospectively, (and even inadvertently) comes the marginalization of the contributions of women to the greater culture.

My short answer for what a 21st-century female composer needs to succeed? The big ones are talent, technique, time, and a support system. It needs to be a financial support system as well as an artistic one, and it needs to provide opportunities for a composer who is a women to be able to hear her music performed. And she needs to hear it performed more than once. She needs to have critical feedback from people who know what they are listening to, and she needs to have her music evaluated in the same way that her male counterparts have their music evaluated. She needs to learn first hand, and in proper acoustics, what works and what doesn't.

Teachers and mentors she has. It is opportunity that helps her grow as a composer.

Nadia Boulanger was, by all accounts, the most important composition teacher of the 20th century. She was also an excellent composer, but she stopped writing after the death of her sister Lili, who was, even as a very young person, one of the finest composers of the 20th century, of either gender. One of the reasons I think Nadia Boulanger devoted herself to teaching rather than to composition was that she felt that, perhaps, she could help develop other composers develop the way she helped Lili develop. Many of her students were women (you can find an incomplete list of her students here.) In addition to her composition students there are a large number of analysis students on the list. A great part of teaching composition is teaching analysis.

From where I sit in the 21st century I can clearly see an early-20th-century trend involving the rise of women as artistic and literary figures as well as important figures in the sciences. (Madame Curie and Rosalind Franklin are two examples that come to mind). And then somewhere in the middle of the century, perhaps around the time of McCarthyism and the prominence of Virgil Thomson as a music critic (click here for google search for the term Virgil Thomson and Misogyny, though most of the material that comes up is from Google Books) women were forced back to the margins of creative culture.

Marion Bauer is an example of a first rate composer who fell victim to Thomson's mysogyny. He deemed her too conservative to be considered an equal to the 20th century composers he admired. I imagine that he found her to be intimidating (she was a far better composer than he was), and that he used his power of influence to try to take her down.

A couple of female-friendly decades followed Thomson's death (friendly to women who were composers and women who did other creative things), and though we don't yet have an Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, at least as of 2009 women are legally entitled to get equal pay for equal work.

I fear the the neo (or pseudo) McCarthyites that have invaded the second decade of the 21st century are trying their darnedest to marginalize women once again. With the marginalization of women as composers, even retrospectively, (and even inadvertently) comes the marginalization of the contributions of women to the greater culture.

My short answer for what a 21st-century female composer needs to succeed? The big ones are talent, technique, time, and a support system. It needs to be a financial support system as well as an artistic one, and it needs to provide opportunities for a composer who is a women to be able to hear her music performed. And she needs to hear it performed more than once. She needs to have critical feedback from people who know what they are listening to, and she needs to have her music evaluated in the same way that her male counterparts have their music evaluated. She needs to learn first hand, and in proper acoustics, what works and what doesn't.

Teachers and mentors she has. It is opportunity that helps her grow as a composer.

Sunday, March 04, 2012

Saturday, March 03, 2012

Male and Female Musicians and Physical Attractiveness

During these first few days of Women's History Month I have been thinking about the role that physical attractiveness seems to play in the careers of women, particularly women who are performing musicians.

Pauline Viardot was, by many accounts (and photos), not a terribly attractive woman. Heinrich Heine wrote (when she still known as Pauline Garcia, before she was married) about her particular type of ugliness:

Amy Beach was not a particularly attractive young woman

(though, as an older woman she did have an unusual sort of beauty), but she was able to achieve remarkable success as both a performing pianist and as a composer. It was her music that mattered, not her looks.

There have been legions of male 20th century performing musicians and composers who would have fit into the "less-than-attractive" category.

This photograph shows one male musician who definitely exceeds the standards of normal attractiveness, and one who certainly falls short of the parameters of normal attractiveness. Both men had tremendous talent, intellect, social skills, and ability, and both had great careers. Copland's looks never hampered his career (and Bernstein's looks never hurt his). The world of music is filled with the faces of men who were, even as young men, particularly unattractive. Of the 20th-century male composers and performing musicians I know with less-than-attractive faces, no one seems to have been unfairly judged as a musician because of his looks.

Women who appear before the public have always been judged by their looks. During the 20th century a man could get away with appearing clean and (sometimes) combed, and be judged by what he said (or in the case of a performing musician, how he played). Some women (and some men) have considered (and still do consider) certain less-than-attractive men tremendously attractive because of their intellect, substance, and power. A less-than-attractive woman has to try to make herself attractive in order for people to even consider her intellect or substance. If she presents the aura of being powerful (and she is not particularly attractive) she becomes particularly suspect. Consider Emma Goldman.

Consider what I call the Boyle Effect. Remember the hubbub that her looks caused, and the subsequent media obsession with her "makeover?" Consider the way Hillary Clinton had to slave over her appearance when she was running for president in 2008, and now that she has proven that her brains are more important in her current job than her looks, she doesn't have to waste her time trying to look 20 years younger than she is.

Now, in the 21st century, it seems that both men and women HAVE to look attractive in order to have careers as soloists. Never in my life have I seen so many photographs of attractive musicians in the "classical" field. Could it be that we are all simply getting better looking because of what we do? I doubt it. Perhaps the photographs are just getting better (not to mention the magic of orthodonture).

Pauline Viardot was, by many accounts (and photos), not a terribly attractive woman. Heinrich Heine wrote (when she still known as Pauline Garcia, before she was married) about her particular type of ugliness:

"She is ugly but with a kind of ugliness which is noble, I should almost say beautiful…. Indeed the Garcia recalls less the civilized beauty and tame gracefulness of our European homelands than she does the terrifying magnificence of some exotic and wild country…. At times, when she opens wide her large mouth with its blinding white teeth and smiles her cruel sweet smile, which at times frightens and charms us, we begin to feel as if the most monstrous vegetation and species of beasts from India and Africa are about to appear before us."All Ginette Neveu had to do to have a performing career (short as it was--she was killed in a plane crash) was play the hell out of the violin. She didn't have to try and glamorize herself.

Amy Beach was not a particularly attractive young woman

(though, as an older woman she did have an unusual sort of beauty), but she was able to achieve remarkable success as both a performing pianist and as a composer. It was her music that mattered, not her looks.

There have been legions of male 20th century performing musicians and composers who would have fit into the "less-than-attractive" category.

This photograph shows one male musician who definitely exceeds the standards of normal attractiveness, and one who certainly falls short of the parameters of normal attractiveness. Both men had tremendous talent, intellect, social skills, and ability, and both had great careers. Copland's looks never hampered his career (and Bernstein's looks never hurt his). The world of music is filled with the faces of men who were, even as young men, particularly unattractive. Of the 20th-century male composers and performing musicians I know with less-than-attractive faces, no one seems to have been unfairly judged as a musician because of his looks.

Women who appear before the public have always been judged by their looks. During the 20th century a man could get away with appearing clean and (sometimes) combed, and be judged by what he said (or in the case of a performing musician, how he played). Some women (and some men) have considered (and still do consider) certain less-than-attractive men tremendously attractive because of their intellect, substance, and power. A less-than-attractive woman has to try to make herself attractive in order for people to even consider her intellect or substance. If she presents the aura of being powerful (and she is not particularly attractive) she becomes particularly suspect. Consider Emma Goldman.

Consider what I call the Boyle Effect. Remember the hubbub that her looks caused, and the subsequent media obsession with her "makeover?" Consider the way Hillary Clinton had to slave over her appearance when she was running for president in 2008, and now that she has proven that her brains are more important in her current job than her looks, she doesn't have to waste her time trying to look 20 years younger than she is.

Now, in the 21st century, it seems that both men and women HAVE to look attractive in order to have careers as soloists. Never in my life have I seen so many photographs of attractive musicians in the "classical" field. Could it be that we are all simply getting better looking because of what we do? I doubt it. Perhaps the photographs are just getting better (not to mention the magic of orthodonture).

3 Minutes of Barber-Hadelich Bliss

Three minutes is just enough to get my atoms to align themselves properly, but oh how I wish it didn't have to end!

Friday, March 02, 2012

Life Imitating Art in The Paper Chase?

Sometimes you find two people who bear remarkable similarities to one another, even though they might come from different centuries and very different cultures. Here's an amusing example.

Then there are fictional characters who bear a remarkable resemblance to real people. We usually assume that those characters were modeled on real people, but sometimes the real person, due to the magic of long-running weekly television programs, can identify with or even model him or herself on a fictional character. Take the fictional character of Franklin Ford III, played by Tom Fitzsimmons, on The Paper Chase television series. Fitzsimmons, who seems to have left the acting business, was born in 1947, a year of birth that he shares with a person who has been appearing daily on television and the internet for the past couple of years.

You can see Fitzsimmons in character on the far right side of this picture (standing, wearing a sweater):

And you can see him in this promo for the DVD of the first season. Pay particular attention at the 13-second mark, the 18-second mark, and the 27-second mark.

The character of Franklin Ford III (known as "Ford" even by his sister) is a legacy at Harvard Law School. His father is a very prominent lawyer and an important financial supporter of the school. Ford's character is rather rigid, he feels superior to his classmates (except for those he knows in his heart of hearts are as capable a law student as he is). He has problems with connecting with his feelings, and his classmates (and his audience) have a certain empathy for him. The character of Ford is, in many ways, a "poor rich guy," because he can't seem to really understand what it means to be a "normal" person.

It is quite remarkable that Fitzsimmons, writers John Jay Osborn, Jr. (who graduated from Harvard Law School in 1970 and must have written the novel on which the movie and television series is based while he was still in school), James Bridges, and director Jack Bender managed to come up with this "cocktail" of a fictional character who turned out to be so similar, in profile (or perhaps the word should be pedigree), style, image, and substance to a person who is very real. On the other hand, there might have been some deep identification with the character of Ford on the part of the person in current public life I'm making reference to (you have figured out by now who he is) when he watched the television series, which ran from 1978-1986. And I imagine he watched it religiously. Perhaps Osborne and Bender followed the career of this public figure, and asked Fitzsimmons to study his mannerisms.

There is the Ford and General Motors coincidence, but that could be neither here nor there. I will say no more, except for the fact that the "heart of hearts" phrase in the above paragraph that describes Ford was a totally unintentional pun (but I'll take credit for it). The main character of the series, and the person who is Ford's main intellectual rival, is named James T. Hart.

Then there are fictional characters who bear a remarkable resemblance to real people. We usually assume that those characters were modeled on real people, but sometimes the real person, due to the magic of long-running weekly television programs, can identify with or even model him or herself on a fictional character. Take the fictional character of Franklin Ford III, played by Tom Fitzsimmons, on The Paper Chase television series. Fitzsimmons, who seems to have left the acting business, was born in 1947, a year of birth that he shares with a person who has been appearing daily on television and the internet for the past couple of years.

You can see Fitzsimmons in character on the far right side of this picture (standing, wearing a sweater):

And you can see him in this promo for the DVD of the first season. Pay particular attention at the 13-second mark, the 18-second mark, and the 27-second mark.

The character of Franklin Ford III (known as "Ford" even by his sister) is a legacy at Harvard Law School. His father is a very prominent lawyer and an important financial supporter of the school. Ford's character is rather rigid, he feels superior to his classmates (except for those he knows in his heart of hearts are as capable a law student as he is). He has problems with connecting with his feelings, and his classmates (and his audience) have a certain empathy for him. The character of Ford is, in many ways, a "poor rich guy," because he can't seem to really understand what it means to be a "normal" person.

It is quite remarkable that Fitzsimmons, writers John Jay Osborn, Jr. (who graduated from Harvard Law School in 1970 and must have written the novel on which the movie and television series is based while he was still in school), James Bridges, and director Jack Bender managed to come up with this "cocktail" of a fictional character who turned out to be so similar, in profile (or perhaps the word should be pedigree), style, image, and substance to a person who is very real. On the other hand, there might have been some deep identification with the character of Ford on the part of the person in current public life I'm making reference to (you have figured out by now who he is) when he watched the television series, which ran from 1978-1986. And I imagine he watched it religiously. Perhaps Osborne and Bender followed the career of this public figure, and asked Fitzsimmons to study his mannerisms.

There is the Ford and General Motors coincidence, but that could be neither here nor there. I will say no more, except for the fact that the "heart of hearts" phrase in the above paragraph that describes Ford was a totally unintentional pun (but I'll take credit for it). The main character of the series, and the person who is Ford's main intellectual rival, is named James T. Hart.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)