I have a vivid visual childhood memory (a cinematic one, filmed from above) of sitting in my closet with a pack of Zener cards and testing my ESP (extra sensory perception). I hoped that if I worked hard enough at it, I would be able to "see" the images on the cards before turning them over. I knew nothing about random success rates, and was unable understand why I could sometimes be right, or that I could "visualize" something that ended up being wrong. I was still at an age of magical thinking. I also, thanks to a Tarot card reading given to me by my aunt, had no reason to believe that there wasn't something special about that deck of brightly-colored cards that could see the relationships of past and future events in my young life.

I still appreciate the intuition that can happen during a Tarot card reading (or an astrological chart reading), but in adulthood I have come to understand with full conviction that the future is something that we encounter step by step, and not something that can be reliably predicted. We can do our best to prepare for events that we know are coming (like rehearsals, concerts, interviews, tests, meals, or competitions), and being prepared for those events helps us be prepared for other future events. We can make the most educated of guesses about the future, but there is no way of really knowing what will happen. And no matter how much we want it to be possible, time travel to the future isn't possible, because the future isn't there yet. There's no there there.

We can use our senses to figure out that it might rain. It can smell like it's going to rain, it can feel like it will rain, it can look like it might rain, and the activity of the birds can even sound like it might rain. (You can look at the weather on your phone, but that's cheating.) We can use context clues and and our understaning of human nature to make guesses about the future, but uttering the phrase, "I knew it" is very often the result of having put conscious and unconscious sensory clues together.

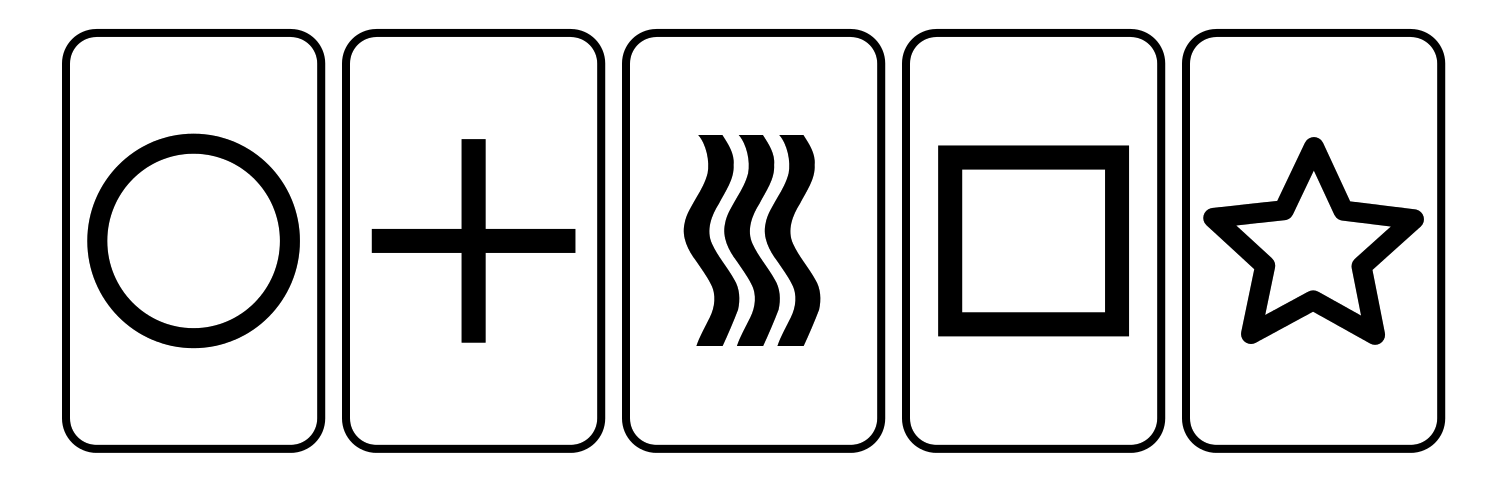

There are five physical senses we know about, and each works on a continuum. There are also "senses" that use combinations of the physical senses like sense of direction, sense of time, sense of security, and sense of rhythm (I'm not sure that there is a physical basis to having a sense of purpose or a sense of humor). And then there are things that don't make sense. We talk about sensitivity, and explore the sensual. We talk about good taste, bad taste, and questionable taste, while we rely on the physical sense of taste to determine whether something we eat is appealing or deadly. "It left a bad taste in my mouth" is almost never used literally.

Some people have such an acute sense of smell that they can use it to identify disease, and some people have no sense of smell. Some people have such an acute sense of pitch that they can identify notes in a cluster, and some people cannot hear anything at all. Some people have very little connection with what their hands might be doing ("I'm all thumbs") and some people have developed enough sensitivity in their fingertips to read Braille, allowing their sense of touch to compensate for lack of vision.

Some people who do not have the physical ability to with their eyes have the ability in their brains to visualize, and some people who do have the ability to see are unable to "see" images in their brain. Some people have photographic memories that they can rely on in circumstances that call for attention to detail, and some people (like me) only have a vague visual memory of where something might be on a page.

Through practicing musicians develop eyes that hear and ears that see (connections between the senses). We use our eyes to allow our mind's ear to hear what the next note is going to sound like. We also make connections between our eyes, ears, and sense of touch to measure the distance our arms and hands need to travel to produce the pitches that our eyes tell our ears to "see."

Some people "see" letters as colors, and some people hear musical pitches or musical keys as colors. I, being neurotypical in this regard, have never experienced this, but I do find that I can react emotionally to colors I can see as well as to colors that I imagine. Musicians often talk about the "color" of a voice, or about changing the "color" of a note when we try to describe the way we shape the sound waves with our instruments or voices. Perhaps we use "color" because we imagine that most people would be able react to that word, and understand what we mean when we try to use words to describe timbre.

I recently learned of a condition called Aphantasia, which is the inability to create mental images. I learned about it from Neesa Suncheuri, a violist with the condition, who is interested in exploring musical posibilities that relate to her experience. Since I am always looking for ways of extending my vocabulary as a composer, I was very excited to write a piece for solo viola that, in my inexperienced-with-the-inabiity-to-visualize mind's eye, might resonate with Neesa's experience. I have done a lot of reading about Aphantasia (there's even a very active reddit group), but I haven't found discussions of the condition among "classical" musicians. The study of this is very new, and I hope that my piece will help promote some discussion among musicians.

I named my piece "Aphantasia and Fugue State" because I find it really difficult to resist a musical pun (or two).

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment