I spent the autumn of 1981 in Vienna, Austria. I left a teaching job I had in a little mountain town, and found myself enrolled as a student at the Hochschule studying recorder. I also developed an interest in jazz, and thought that it would be interesting to learn how to improvise like a jazz musician. A friend of mine recommended that I go and hear a jazz pianist named Fritz Pauer, so I went to a jazz club where he was playing (Vienna was awash with Jazz clubs in the early 1980s). I found myself sitting at a table with an American, so I introduced myself. After establishing the "wheres" of our American-ness, I told him that I was a flutist. He beamed. He was one too. When I told him that I studied with Julius Baker he was in awe. Julius Baker was his favorite flutist.

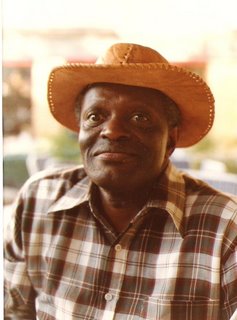

This man was Leo Wright. He was at this particular jazz club because his wife Ellie Wright was singing there. She sang in a wonderful stylized English that completely masked the fact that she was from Vienna.

Leo was in his early 50s and was in the process of recovering from a stroke. He had difficulty moving his right hand, but he was determined to get his playing back. In his prime he was one of the most versatile saxophonists around, as well as an extremely agile flutist. He had a huge international career, playing with Dizzy Gillespie in the 1960s, and making wonderful recordings. By the end of the evening we agreed to trade lessons. I would try to teach him to play the flute like Julius Baker, and he would try to teach me to swing. In order to accomplish these tasks we spent a lot of time together.

He was kind of like a surrogate father to me in Vienna. He and Ellie taught me to be proud of my American-ness. Ellie encouraged me to read Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer which set me firmly on the path towards becoming a reader and loving literature.

I taught Leo to breathe by using his diaphragm. He never had adequate flute lessons (it seems that people didn't know much about the function of the diaphragm in playing the flute before the 1970s) and never learned to breathe properly. I believed that there would be a connection between this new (for him) type of breathing and his ability to relax and re-connect musically with his right hand. Somehow this connection worked. Eventually he was able to play again, and he made a big comeback several months after I left Vienna.

Leo used to bring me to jazz clubs all the time, and he used to encourage me to sit in with the musicians who were playing. Everyone respected Leo, so I guess they took a chance on me. I might have made a serious fool of myself, but Leo never let on that he thought so. I still learned a lot from Leo. As far as my learning to "swing" was concerned, I learned to appreciate good jazz playing, but I have never been able to play like a jazz musician myself.

I learned about dedication from Leo. Even when he was unable to use his right hand at all, Leo practiced long tones on the saxophone using only his left hand. I learned from Leo that the spirit of a musician is a very strong thing, and that a that the power of positive thinking is far stronger than I ever imagined it could be. I also learned about the particular strengths that I had myself.

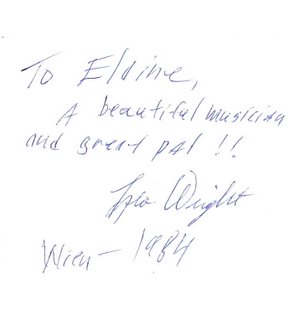

Music is hanging around the air in Vienna. It always has been there, and it probably will always be there. Fritz Pauer told me that it has something to do with the water that flows in the underwater canals. Even in the silence of the night in Vienna, there is a certain musical rhythm in the air. Anyway, one day while I was walking in Vienna I started singing a tune. I figured it must have been something that I heard, but I couldn't place it. I sang it for Leo, and he had never heard it before either. He helped me harmonize it with jazz chords, and I let it rattle around in my brain for about 20 years until I turned it into a piece for string quartet that I called "Good-bye to Vienna." Of course I dedicated it to Leo, who is no longer alive in body, but will always be alive in spirit.